Wie verschiedene Webseiten in den letzten Tagen berichteten (s. nur hier und hier), hat der US District Court Western District of Washington (ein Bundesgericht) in der Sache „Elf-Man vs. Cariveau et al“ eine „Order Granting Motion to Dismiss“ erlassen, die sich mit der Beweisführung mittels IP-Adressen in den USA befasst (Volltext via Scribd hier).

1. Worum geht es?

Das Verfahren Elf-Man gegen Cariveau et al ist ein ähnliches Verfahren wie die hier in Deutschland erfolgenden Abmahnungen und Klagen wegen Filesharings. Die Klägerin Elf-Man LLC ging wegen des Downloads und der Verbreitung des Films „Elf-Man“ über Bittorrent zunächst gegen verschiedene unbekannte „John Does“ vor, wobei sie anfangs nur die IP-Adressen der potentiellen Verletzer kannte. Das Gericht gab dem Antrag auf „Discovery“ statt, so dass die Identität der hinter den IP-Adressen stehenden Anschlussinhaber aufgedeckt werden konnte (vergleichbar unserem Verfahren nach § 101 Abs. 9 UrhG).

This action was filed on March 20, 2013, against 152 Doe defendants. Each Doe defendant was identified only by an IP address linked to the on-line sharing of the movie “Elf-Man.” The Court granted plaintiff’s motion to initiate early discovery in order to obtain information sufficient to identify the owner of each IP address, but …

Plaintiff’s claim of direct copyright infringement relies on a conclusory allegation that the named defendants were personally involved in the use of BitTorrent software to download “Elf-Man” and to further distribute the movie.

Anschließend ging die Klägerin gegen einzeln namentlich benannte Anschlussinhaber vor. Die aber wehrten sich.

On October 3, 2013, plaintiff filed a First Amended Complaint naming eighteen individual defendants. The remaining Doe defendants were dismissed, and default has been entered against two of the named defendants. Four of the named defendants filed this motion to dismiss, arguing that plaintiff’s allegations, which are presented in the alternative, fail to state a claim for relief that crosses the line between possible and plausible.

Als Ergebnis war zu klären, ob die Klägerin tatsächlich mit guten Gründen gegen die Beklagten vorgehen konnte, ob also die Klägerin beweisen konnte, dass die Beklagten auch für die von ihrem Anschluss aus begangenen Rechtsverletzungen verantwortlichen waren:

The question for the Court on a motion to dismiss is whether the facts in the complaint sufficiently state a “plausible” ground for relief.

Die Beklagten stellten entsprechend eine „Motion to Dismiss„, vergleichbar einem Klageabweisungsantrag im deutschen Zivilprozessrecht.

2. Die Entscheidung des Gerichts

Das Gericht weist zunächst darauf hin, dass es bereits bei der Gewährung von Discovery Bedenken geäußert hatte. Diese hätten sich nun verfestigt, daher habe das Gericht dem Antrag der Beklagten stattgegeben. Der Maßstab hierfür ist der folgende (Hervorhebungen durch Verfasser):

To survive a motion to dismiss, a complaint must contain sufficient factual matter, accepted as true, to state a claim to relief that is plausible on its face. A claim is facially plausible when the plaintiff pleads factual content that allows the court to draw the reasonable inference that the defendant is liable for the misconduct alleged. Plausibility requires pleading facts, as opposed to conclusory allegations or the formulaic recitation of elements of a cause of action, and must rise above the mere conceivability or possibility of unlawful conduct that entitles the pleader to relief. Factual allegations must be enough to raise a right to relief above the speculative level. Where a complaint pleads facts that are merely consistent with a defendant’s liability, it stops short of the line between possibility and plausibility of entitlement to relief. Nor is it enough that the complaint is factually neutral; rather, it must be factually suggestive.

a. Täterschaft

Unter Anwendung dieser Grundsätze hat das Gericht nicht erkennen können, dass aus dem Umstand, dass von einer IP-Adresse aus eine Rechtsverletzung begangen worden sein soll, auch zu schließen ist, dass der Anschlussinhaber der Täter der Rechtsverletzung ist (Hervorhebungen durch Verfasser):

Plaintiff’s claim of direct copyright infringement relies on a conclusory allegation that the named defendants were personally involved in the use of BitTorrent software to download “Elf-Man” and to further distribute the movie. The only fact offered in support of this allegation is that each named defendant pays for internet access, which was used to download and/or distribute the movie. As the Court previously noted, however, simply identifying the account holder associated with an IP address tells us very little about who actually downloaded “Elf-Man” using that IP address. While it is possible that the subscriber is the one who participated in the BitTorrent swarm, it is also possible that a family member, guest, or freeloader engaged in the infringing conduct. The First Amended Complaint, read as a whole, suggests that plaintiff has no idea who downloaded “Elf-Man” using a particular IP address. Plaintiff has not alleged that a named defendant has the BitTorrent “client” application on her computer, that the download or distribution is in some way linked to the individual subscriber … plaintiff merely alleges that her IP address “was observed infringing Plaintiff’s motion picture” and guesses how that might have come about. While it is possible that one or more of the named defendants was personally involved in the download, it is also possible that they simply failed to secure their connection against third-party interlopers. Plaintiff has failed to adequately allege a claim for direct copyright infringement.

b. Teilnahme

Auch eine Teilnahme (Mittäterschaft/Beihilfe) an der Rechtsverletzung von Dritten kann das Gericht nicht erkennen:

Plaintiff’s claim of contributory infringement relies on the allegation that the named defendants materially contributed to others’ infringement of plaintiff’s exclusive rights by participating in a BitTorrent swarm. For the reasons discussed above, this allegation of personal involvement in a swarm is conclusory, and plaintiff has failed to adequately allege a claim for contributory infringement.

c. „Indirect Infringement“

Ganz spannend wird die Entscheidung im nächsten Abschnitt namens „Indirect Infringement“, die es unter Hinweis auf die „Grokster“-Entscheidung ablehnt (Hervorhebungen durch Verfasser):

Plaintiff alleges that the named defendants obtained internet access through a service provider and “failed to secure, police and protect the use of their internet service against illegal conduct, including the downloading and sharing of Plaintiff’s motion picture by others.“ …

Plaintiff argues, however, that contributory infringement is a judge-made concept and the Court should entertain its admittedly novel theory of liability – that defendants can be held liable for contributory infringement because they failed to take affirmative steps to prevent unauthorized use of their internet access to download “Elf-Man” – so that this area of the law can develop fully. While it is true that the circumstances giving rise to a claim of contributory infringement have not all been litigated and that courts will continue to analyze contributory liability claims in light of common law principles regarding fault and intent (Perfect 10, 487 F.3d at 727), plaintiff’s theory treads on an element of the claim that has already been fixed by the courts, namely the requirement that defendant’s contribution to the infringement be intentional (Grokster, 545 U.S. at 930).

d. Fazit, Vergleich mit Entscheidung des US District Court of Eastern New York und Kontext

Die Kernaussage des Gerichts ist dementsprechend, dass – selbst wenn man zugrunde legt, dass eine Rechtsverletzung von einem Internetanschluss mit einer bestimmten IP-Adresse aus begangen worden ist – nicht feststeht, wer die Rechtsverletzung begangen hat. Das Gericht sieht es vielmehr als den Normalfall an, dass es zumindest möglich ist, dass ein Dritter über den Internetanschluss die Rechtsverletzung begangen hat.

Ähnlich hatte schon der US District Court – Eastern District of New York (ein anderes US-Bundesgericht) im Jahr 2012 die Rechtslage beurteilt und damals ausgeführt (Hervorhebungen durch Verfasser):

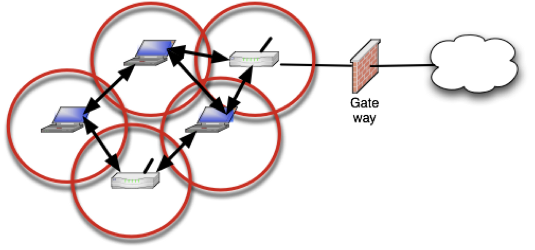

Indeed, due to the increasingly popularity of wireless routers, it much less likely. While adecade ago, home wireless networks were nearly non-existent, 61% of US homes now havewireless access. Several of the ISPs at issue in this case provide a complimentary wireless routeras part of Internet service. As a result, a single IP address usually supports multiple computer devices – which unlike traditional telephones can be operated simultaneously by differentindividuals.See U.S. v. Latham, 2007 WL 4563459, at *4 (D.Nev. Dec. 18, 2007). Different family members, or even visitors, could have performed the alleged downloads. Unless the wireless router has been appropriately secured (and in some cases, even if it has been secured), neighbors or passersby could access the Internet using the IP address assigned to a particular subscriber and download the plaintiff’s film. …

In sum, although the complaints state that IP addresses are assigned to “devices” and thus by discovering the individual associated with that IP address will reveal “defendants” true identity,” this is unlikely to be the case. Most, if not all, of the IP addresses will actually reflect a wireless router or other networking device, meaning that while the ISPs will provide the name of its subscriber, the alleged infringer could be the subscriber, a member of his or her family, an employee, invitee, neighbor or interloper.

Im Ergebnis ist das hier besprochene Gerichtsverfahren paralleler zu den deutschen Filesharing-Abmahnungen zu sehen. Nachdem es insbesondere in Deutschland so wunderbar geklappt hat, Filesharing-Nutzer durch eine Vielzahl von Abmahnungen und Rechtsstreitigkeiten vom Filesharing abzubringen, versuchen Rechteinhaber in den USA ein ähnliches Vorgehen – allerdings unter anderen rechtlichen Vorzeichen, da dem US-Recht die Störerhaftung nach deutschem Konzept weitgehend fremd ist. Ausgeglichen werden kann/soll das offenbar durch das Rechtsinstitut des „Indirect Infringement“, bei dem dem Anschlussinhaber die fehlende Sicherung des Anschlusses zum Vorwurf gemacht wird.

Bei der Bewertung des Urteils muss man sich allerdings vor Augen halten, dass hier zwar ein Bundesgericht entschieden hat, aber lediglich das für den Distrikt Washington zuständige. Die USA haben 11 solcher Distrikte mit verschiedenen Gerichten. Für IT/IP-Sachverhalte wird insbesondere auf die Gerichte des Distrikts Kalifornien (inkl. Silicon Valley) geschaut. Immerhin sind aber nun schon zwei Bundesgerichte im Wesentlichen der gleichen Auffassung …

By Tintazul (Map) / ChristianGlaeser (text) [Public domain or CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

3. Vergleich mit deutscher Rechtslage und deutschen Gerichtsverfahren

Das vorliegende Urteil gibt auch Anlass, einen Vergleich zum Umgang deutscher Gerichte mit IP-Adressen zu ziehen. Erst kürzlich hat der BGH wieder Stellung zur Beweisführung in Filesharing-Prozessen genommen (BGH, Urt. v. 8.1.2014 – I ZR 169/12 – Bearshare, die Urteilsgründe liegen noch nicht vor).

Die Linie des BGH (und der Instanzgerichte) ist grundlegend anders als bei den beiden o.g. US-Gerichten. Der BGH geht nämlich davon aus, dass eine tatsächliche Vermutung dafür besteht, dass für eine Rechtsverletzung, die von einem Internetanschluss ausgegangen ist, der Anschlussinhaber verantwortlich ist (so z.B. BGH MMR 2013, 388 Rn.?33 – Morpheus). Der BGH kommt auf diesem Wege zu einem sehr pragmatischen Ergebnis. Mit der auf die Vermutung folgenden sekundären Darlegungslast wird nämlich dem Rechteinhaber seine tatsächliche Beweisschwierigkeit (er kann anhand der IP-Adresse schlicht nicht darlegen, wer die Rechtsverletzung tatsächlich begangen hat) etwas erleichtert, der Anschlussinhaber muss seinerseits Umstände darlegen, die seine Täterschaft in Zweifel ziehen, um die angestellte Vermutung zu erschüttern.

Die Vermutung des BGH steht allerdings, wie die US-Gerichte deutlich aufzeigen, auf tönernen Füßen (s. auch Mantz, Anmerkung zu AG Frankfurt, Urt. v. 14.6.2013 – 30 C 3078/12 (75), MMR 2013, 607). Denn (auch unter Hinweis auf die US-Entscheidungen) kann man durchaus die Auffassung vertreten, dass es heutzutage den Normalfall darstellt, dass ein Internetanschluss durch eine Mehrzahl von Personen genutzt wird (Familienmitglieder wie in den BGH-Entscheidungen Morpheus und BGH Bearshare, WG-Mitbewohner, Nachbarn, Kunden etc.), die dann aber genauso wie der Anschlussinhaber als potentielle Täter in Betracht kommen. Wenn aber schon die Grundlage einer Vermutung (IP-Adresse = Anschlussinhaber) nicht besteht, kann zu Lasten des Anschlussinhabers auch keine sekundäre Darlegungslast greifen. Soweit ersichtlich, sind bisher aber weder der BGH noch andere Gerichte von dieser Linie abgerückt. Allerdings setzen die Gerichte die Anforderungen an die sekundäre Darlegungslast und die Pflichten des Anschlussinhabers (zumindest im familiären Bereich) immer weiter herunter – wie eben in BGH Morpheus und Bearshare. Die Rechtsentwicklung ist hier aber noch lange nicht am Ende angelangt. Denn noch immer stehen Entscheidungen zu anderen Mitbenutzungen (WGs etc.) und zu gewerblichen Anbietern (hierzu zuletzt LG Frankfurt, Urt. v. 28.6.2013 – 2-06 O 304/12 – Ferienwohnung; dazu Mantz, GRUR-RR 2013, 497) aus.

Im Zusammenhang mit IP-Adressen siehe auch Gietl/Mantz, Die IP-Adresse als Beweismittel im Zivilprozess – Beweiserlangung, Beweiswert und Beweisverbote, CR 2008, 810 (PDF, 0,2 MB, CC-BY-ND).

Post teilen / share post: (wird möglicherweise durch Tracking-Blocker geblockt / may be blocked by tracking blocker such as Ghostery)

#IP_Adresse als #Beweismittel (in US-Verfahren) #Anschlussinhaber = #Täter eine Rechtsverletzung? von @offenetze http://t.co/9bJDPpGmec